Story by Jessica Mehre

Take a moment to picture your favorite day. This could be a day you already experienced, perhaps a wedding or graduation ceremony. Or it could be a hypothetical perfect day, with the sun shining, close friends around, and a fun activity to enjoy.

Odds are, that perfect day is set in a place—a town, a part of the country, a room in a house, or a region in a state. My perfect day is back home at my parents’ farm in Greenbush, Wisconsin. It’s sunny with a slight breeze and 75 degrees on the dot, the perfect conditions to go for a run around the block and see fields start to green.

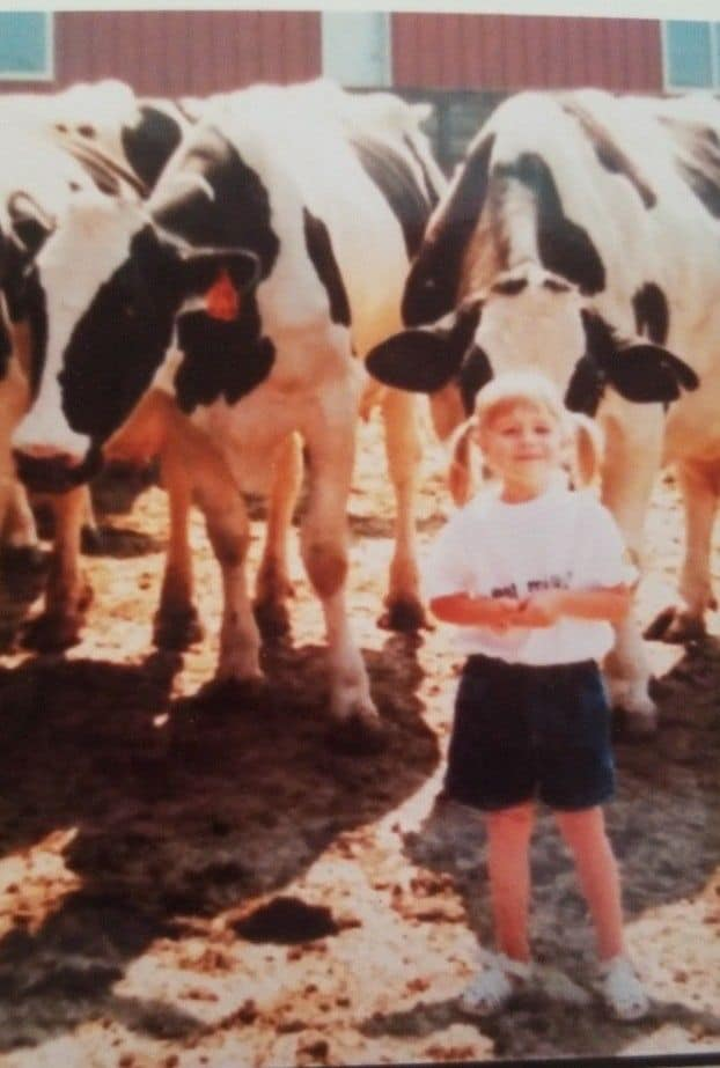

I don’t consider myself a sentimental person. But, when it comes to that farm, I make an exception. That farm—where I spent hundreds of hours listening to the local oldies station while my dad and I milked cows, where my grandparents tried their best to teach me sheepshead, and where I earned a few scars—continues to shape my world view and motivate the research I conduct.

Now, you don’t need to be as intrinsically connected to a place as a farm kid is to their home farm to understand that place matters. A place creates the context for our lives. It’s hard to go skiing if you don’t have cold weather, and it’s hard to grow alfalfa if you don’t get a lot of rain (though not impossible, e.g., New Mexico).

On a deeper level, the specific place where we exist guides how we act by giving clues to what is right and what is wrong, what is possible and what is not. Where I live now in Madison, social norms and institutional structures tell me that driving three miles to campus is wrong. A free student bus pass, easily accessible bike paths, and incredibly expensive campus parking tell me that it’s best to not drive; not to mention, my social circle would furrow their brow at a person who wastes gas for a 3-mile drive.

In the same way, social norms, economic forces, and institutional structures guide how farmers implement management practices and cropping systems in the Upper Midwest. Where I’m from, maintaining weed-free fields, dark green corn that’s taller than your neighbors’, and clean farmyards let people know that you’re doing it right.

You’ll get paid for the grain you harvest and the milk your cows produce; you might get a public incentive to implement cover crops, no-till, and buffer strips. However, if I were to convert my farm’s 100 acres of row crops to rotationally grazed pasture to raise grass-fed beef, I might be met with more resistance on social, economic, and institutional fronts.

I might expect comments like, “She does things differently, I guess.” The market for grass-fed beef would be harder to sell into than the commodity grain and livestock market. Not to mention, I would not receive any payment for ecosystem services, including the soil erosion and nutrient run off that cropland conversion to grassland prevents.

By continuing to grow and incentivize weed-free fields of corn, soybeans, and alfalfa, the place where I grew up continues to signal that this rich land is meant to cultivate crops. The establishment of perennial pastures challenges the assumption of what is right and what is wrong, what is possible and what is not.

This challenge is where my PhD research lies. Within the field of human geography (which broadly studies the interaction between people and the environment), I employ a theory of relational place-making. I am asking: How would a transition from row crops to perennial pasture in eastern Wisconsin, where I grew up, challenge what it means to live and farm in eastern Wisconsin?

Place-making, this never-ending process that informs what a place “is” to a person or a group of people, requires attention to detail. Is eastern Wisconsin a place for tradition? For innovation? Is it a place for high yields, grassland birds, or both?

To start to answer these questions, I’ve listened to farmers and conservation professionals in the area to understand what eastern Wisconsin is to them. Last month, this culminated in a “Meeting of the Minds,” where I was able to present themes of what I heard about eastern Wisconsin agriculture to the same people I had interviewed. From those engrained in the community, I gained a clearer picture of what the region “is” to them and what sort of research, knowledge, and activities can advance both my theoretical questions and the community’s agricultural goals.

In Grassland 2.0 language, I’ve taken the first few steps in developing a “Learning Hub” in east-central Wisconsin, a place and space where people can think about long-term agricultural planning with social and environmental goals in mind.

This process of developing a learning hub has created a new place for me, as well. What eastern Wisconsin means to me is changing.

More than just the place that used to be a dairy farm, I see an escape from the noise and high prices of Madison life, a progressive community collaborating across county lines to solve watershed-wide issues, a place with clean lakes, good schools, and a welcoming environment to guests and locals alike.

While I’ve brought just a sliver of the Grassland 2.0 energy to eastern Wisconsin, I’m hopeful that this new collaboration leads to long-term clean water, vibrant rural communities, and profitable farms in Greenbush and beyond.